Exploring JavaScript's types

You’ve seen the hype around TypeScript and are wondering exactly how these types help us programmers out. If you’ve made it this far into your career without learning about intuitionistic type theory or what T = ∃X { a: X; f: (X → int); } means, that’s just fine. There are plenty of fantastic languages out there that don’t require knowing what a “type” is, so it’s possible to get quite far without diving into the complicated stuff. For the record though, I have no idea what those things are either, I just ripped them off Wikipedia.

Anyway - on to TypeScript, a much more approachable typed language.

What’s a ‘type’?

A ‘type’ means ‘some category of value’ and is usually assigned to a variable. We can say “this variable will contain a number” with the following syntax:

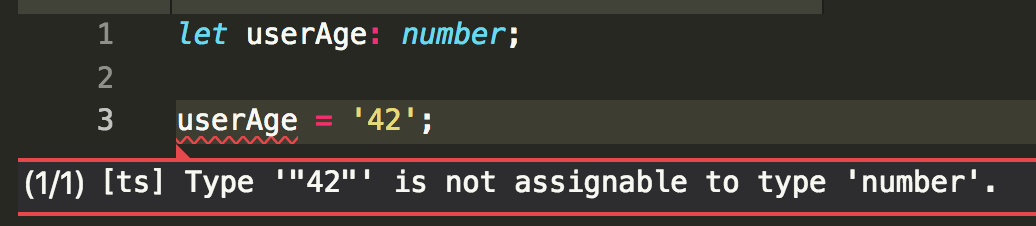

let userAge: number;

At this point, we haven’t defined what someVariable is, just that it can only contain a number. If we try to stick something in there that isn’t a number, then we’ll get a big ol’ complaint from TypeScript:

The angry red squiggle here is because we’ve told TypeScript that userAge is a number and what we’re assigning is a string. No need to worry about structural type systems vs nominative type systems, this is all stuff you probably know already but lacked the vocabulary to explain.

There’s a whole bunch of types that come out of the box in the JavaScript language:

- String

- Number

- Boolean

- Null

- Undefined

- Object

- Symbol (added in ECMAScript 6)

These types are known as primitive types because they’re the basic building blocks every other type is made up of. They’re a bit like the elements in physics. The typeof operator will return a string definition of the type…mostly.

Most of these are pretty straightforward, number is a number, boolean is true or false and Symbol is something fancy to give conference talks about. (Kidding - Symbol does have its uses but that’s another post). The most important type here is Object: A variable that has properties of its own. Each property can have its own type. However, there’s a few surprises in this list: there’s no array or function and undefined and null are separate types.

null vs undefined

Mostly, null and undefined were both added to the language because it was whipped together so fast. Some argue that only one is needed (both represent “there’s nothing here!”) but they’ve come to mean different things. null is deliberate - the programmer has intentionally set this variable to nothing. undefined means that no value has been set yet. This is just a convention, so don’t expect everyone to agree on it.

Where’d array and function go?

There are two big omissions in the list of primitive types. They certainly still exist, but this is one of the quirks of JavaScript, thanks version 1 to being defined in a little less than 2 weeks. Technically speaking, both array and function are of type Object, though the typeof operator kinda gets this right:

let arr = [];

let fn = function () {};

typeof arr; // 'object'

typeof fn; // 'function'

In JavaScript, arrays and functions are just objects with some special abilities added on, which is why the following works:

let arr = [];

arr.foo = 'bar';

We just added an entirely new property to this array instance! We can do this because an array is still an object, and objects let us define arbitrary properties. (TypeScript will still get mad at you). Arrays are “An object that can contain a list of things and has some methods and properties related to that” and functions are “an object that can be called (that is, do something when parentheses are added)”. Both of these are built by starting with an object and adding some extra properties onto it.

Assigning types in TypeScript

In TypeScript, a colon is used to indicate a type definition, like above with let userAge: number. An array of things can be defined by adding square brackets after whatever type of thing it is, so an array of numbers is defined by let userAges: number[]. Functions are usually defined at the time of assignment (see Type Inference below) but in a pinch can be assigned as such:

// takes an int and returns a string

let func: (val: number) => string;

The special any type

JavaScript is a loose language (to put it politely) and so sometimes we may just throw our hands up and say “I have no idea what type this is!” In that particular case, TypeScript provides the any type.

let numArr: number[] = [];

// legal

numArr.push(17);

// illegal

numArr.push('hello');

let whateverArr: any[] = [];

// both legal

whateverArr.push(17);

whateverArr.push('hello');

// It's still an array though!

let error = whateverArr + 17;

Creating your own types

This set of primitive types is great to start out with, but any serious application will need to define its own types. Fortunately, that’s provided through the type keyword - used like let or const but for declaring a type. For instance, the previous post had an array of user objects:

let users = [{

id: 7,

firstName: 'Robert',

lastName: 'Smith'

}, {

id: 12,

firstName: 'Dana',

lastName: 'Jones'

}];

In this case, a user is an object, and that object has three properties, two strings and a number. (Starting to see how we build more complex things from primitive types?) Adding in the type looks like this:

type User = {

id: number;

firstName: string;

lastName: string;

};

let users: User[] = [{

id: 7,

firstName: 'Robert',

lastName: 'Smith'

}, {

id: 12,

firstName: 'Dana',

lastName: 'Jones'

}];

A little more verbose, but this means that the users array will be used consistently around your entire application and catch a whole bunch of bugs before they get a chance to mess everything up (for instance, typing userId when you meant id). The larger the application (and the team working on it) the more powerful these benefits become.

Type Inference

If all this talk about defining all these kinds of types sounds tedious, don’t worry! TypeScript is smart enough that it can figure out most types without any input from you.

// TS knows age is just a number

let age = 42;

// Even without type definitions, this will cause an error

let display = 'I am ' + age + ' years old';

Finally

If you have a headache, I don’t blame you. This was supposed to be simple, and then JavaScript has to make things all complicated with the various asterisks and exceptions. Unfortunately, it gets worse. Next week, we’ll talk about how to use generic types and create our own version of an array.